What's in a Label?

“Information is power. Disinformation is abuse of power.”

– Newton Lee

ARTICLE SUMMARY

Labels matter because they provide a multitude of benefits from communication to comparison to cost-effective marketing. Five types of labels are prevalent – safety, identity, health, certification, and ethics. Despite being substitutes, animal products and alternative protein products are subject to different rules and regulations. Further, labelling regulations are inconsistent across products and regions, creating confusion and limiting access to alternative proteins. Label disparities range from being regulated to unregulated, with varying degrees of clarity and specificity. As we enter an era of greater product choice and complexity, regulators must respond with simple, fair, universal labelling guidelines to protect and educate consumers.

Imagine walking into a grocery store and trying to buy milk, except it isn’t called milk. The dairy aisle is instead an endless row of blank cartons and bottles with no labels. You pick up a product and wonder, is this milk or cream or creamer or a yoghurt drink? Without a label, there’s no way of knowing. Is the product from an animal, or plant, or microorganism, or cells? Once again, there’s no answer. Labels, mundane as they may be, serve an essential purpose. However, for a nascent industry like alternative protein that is trying to find its footing, labels wield even greater power. As a key factor in any purchasing decision, labels will play a key role in defining the future of the industry.

Why Food Labels Matter

The label is a multipurpose product marketing tool whose importance cannot be overstated. The trifecta of benefits provided by labels are (a) communication, (b) comparison, and (c) cost-effective marketing. The emergence of superstores has diffused communication between the seller and the customer. Grocery stores hire limited staff to protect their razor-thin margins. In-store advertising is a cost-intensive endeavour. The most efficient marketing method then becomes product packaging, using labels to establish a connection and secure a sale. The label is used to indicate the product’s identity, contents, benefits, differentiation, affordability, and even company values.

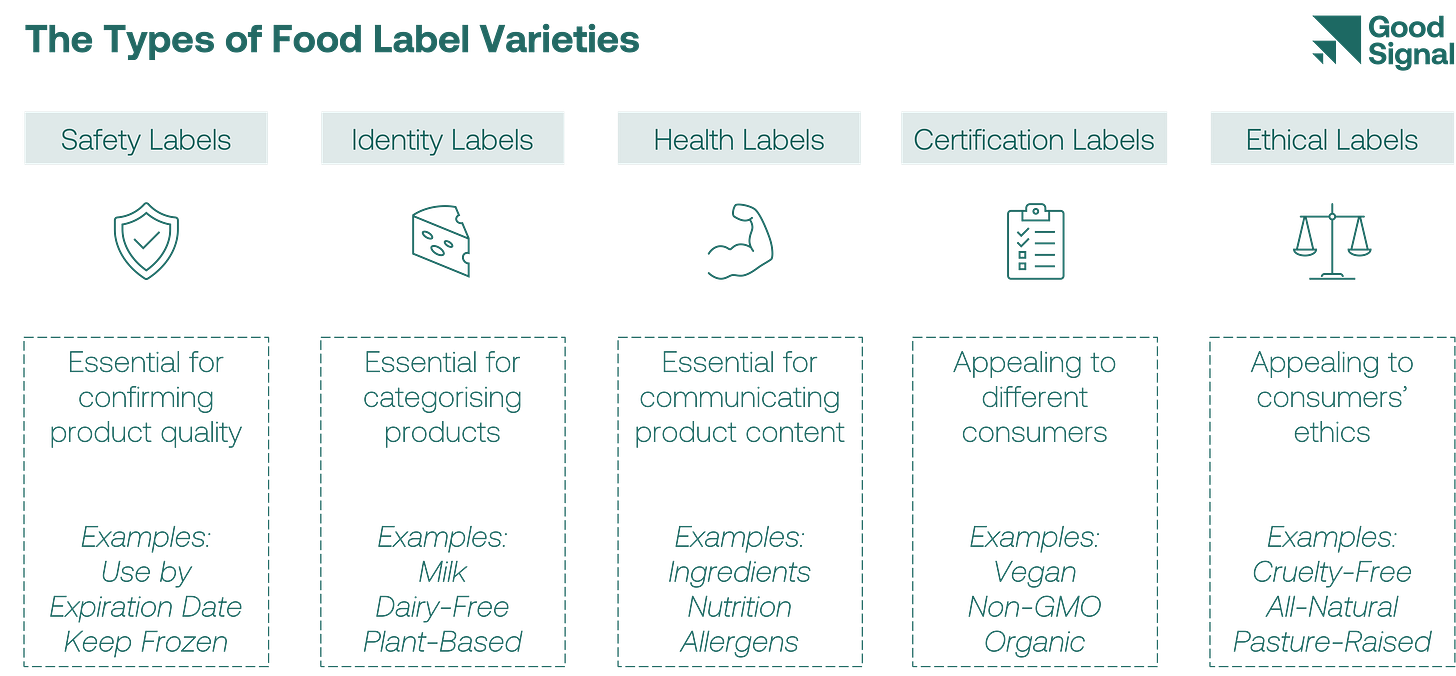

Five types of labels are prevalent – safety, identity, health, certification, and ethics. Together, they deliver a panoply of information to the consumer.

Safety labels include product dating and storage information (e.g.: ‘Use by’ or ‘Expiration date’) which vary by country but are commonly found on food items especially, perishable foods. These specify the need to consume products before the date.

Identity labels communicate basic product information such as product type, source, and technology. For example, ‘plant-based oat milk’ is an identity label with a product type (milk), source (oats) and technology (plant-based).

Health labels focus on nutrition, allergens, and ingredient information. The ingredients are listed in descending order from highest to lowest concentration. Nutrition information is provided in terms of calories per serving or as a percentage of the daily recommended intake. Finally, allergen warnings are required by law in most countries. This applies mainly to key allergens such as gluten, nuts, and soy. In the U.S., for example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines 8 major allergens which must be specified1.

Certification labels highlight specific certifications obtained by the product by adhering to the pre-set requirements of the authorizing organizations. For example, in Singapore, the halal certificate can be obtained by adhering to the requirements set by the Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS). Alternatively, independent organisations such as V-Label create their own criteria for companies to obtain vegan certification. In the U.S., the non-GMO stamp is a certification label regulated by the FDA.

Ethical labels reflect adherence to certain ethical standards that are internally set and ratified. Examples include cruelty-free, eco-friendly, and humanely grown. Since there is often no universal definition, labels can mean whatever companies want them to mean. Thus, consumers rely on the companies to ensure the label is being accurately represented.

A Labelling Conundrum

Animal products and alternative proteins are intended to be substitutes for one other, but access to labels is vastly different for the two industries. The animal products category is governed by regulations that give the industry far more power and flexibility compared to the alternative protein sector. Ideally, both industries should have fair and balanced access to labels, should be able to communicate with consumers, allow them to compare products, and make the best choice from a variety of alternatives.

Various examples of this difference in access are present globally. Initially, the United States state of Missouri implemented a law to make ‘misrepresentation’ of a product as meat illegal if it was not ‘derived from harvested production livestock or poultry’. Since then, 26 states followed suit and introduced 45 bills all pertaining to the labelling of alternative meat and dairy. Of these, 17 laws were enacted in 14 states2. Naturally, the introduction of such laws led to opposition from alternative protein lobby groups demanding fair and balanced labelling regulations. The U.S. Congress introduced the Real MEAT Act requiring alternative protein products to be identified as an ‘imitation’, but this law has not been passed3. Draft guidelines from the FDA issued early this year allowed plant-based beverages to use milk as a descriptor, recommending that they pair it with a nutritional comparison to dairy milk on the packaging. Pushback from both traditional dairy entities, as well as plant-based milk companies, led to the FDA extending the deadline for comments4.

In the European Union, France introduced a law banning the use of ‘meaty’ terms such as burger, filet, and sausage on vegan product labels. The French authorities are now in talks with the EU to understand if such a law would be permissible across the region5. A similar regulation introduced in Belgium is pending a final decision6. In the EU and United Kingdom, laws restricting the labelling of plant-based milk products were introduced leading to oat milk being sold as an ‘oat drink’ in the country7. In Australia and New Zealand, the Food Standards Code allows for alternative products to be labelled using the usual terminology provided that the relevant qualifiers are also included. Still, the farmers regularly express their disdain and lobby the government to introduce stricter laws8. Canadian law prohibits the use of terms such as plant-based cheese, sausage or patties for alternative products. However, Protein Industries Canada has partnered with several other organisations in an attempt to modernise this regulation9. South Africa also imposed a ban on ‘meaty’ names for plant-based products and ordered grocery store Woolworth’s to remove the JUST Egg products from shelves. Although enforcement of this law was slated to begin in May 2023, no updated announcements have been made yet10.

Ambiguity vs Clarity

The bottom line is that the regulations are already restrictive in nature. Further, their variance from one country (or state) to another only makes it harder for plant-based companies to track and update their labels and packaging continually to meet the myriad of requirements. In addition, most regulations target identity labels crucial in ensuring that the consumer finds the product they want. Most regulations are intended to protect consumers, ensure they are not misled, and products are not misrepresented. It is confounding that an identity label such as ‘oat milk’ could be considered misleading, given the ambiguity in numerous animal product labels.

Labels that are regulated and enforced tend to be clear, such as ‘naturally raised’ and ‘antibiotic free’. However, labels that are regulated via loose, unenforced definitions tend to be ambiguous. The organic label in the U.S. is an outlier that undergoes significant scrutiny yet may be unclear to consumers. Based on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) definitions, the ‘100% organic’ label may be used by companies if all ingredients used in the product are organic and the product itself must be certified organic and hold the USDA organic seal. However, if companies don’t meet those requirements, they may use the label ‘organic’ if 90-95% of the ingredients are organic and the label ‘made with organic’ if 70-94% of the ingredients are organic11. Clearly, the organic label is highly regulated, but the lack of awareness between the various organic label types also makes it unclear. Some more examples of ambiguous labels in the U.S. market include:

Free-range, as defined by the USDA, refers to chickens raised with access to the outside for over 50% of the animal’s life12. However, the rules do not expressly state what qualifies as the ‘outside’ and no quality requirements are indicated.

Pasture-raised and humanely raised have no legal definitions issued by either the USDA or FDA. So industrial farmers can set their own criteria and the definition of pasture-raised can differ from farm to farm.

All Natural means that no artificial ingredients or colourants were added to the finished product. This has nothing to do with what the animal was fed and how it was treated. Naturally raised has an actual certification program which ensures that no growth stimulants or antibiotics are administered to the animals. However, the rule does not apply to parasite control; the animals are regularly dipped and showered in chemical disinfectants. The USDA Never Ever Program is the only one that ensures that livestock never receive antibiotics or hormones at any time.

Cage-free egg-laying hens not kept in battery cages may be labelled as such. This does not mean that the hens get to live freely; they are kept in overcrowded warehouses, just not in cages.

‘Wild’ and ‘Wild-caught’ seafood have definitions for labels from the FDA, but they are not well-enforced.

In Singapore, labels such as hormone-free, no growth stimulants, antibiotic-free, and fed no antibiotics are not allowed because the government considers these claims to be misleading in nature13. Similarly, Australian poultry has been hormone-free for the past 40 years, but companies continue to use other claims, such as free-range, which are not regulated14. The following chart summarizes the clarity (and ambiguity) of popular labels in these sectors:

Loose definitions and sparse enforcement have only accelerated the use of ambiguous labels. According to SPINS data, meat products with animal welfare claims (such as the unregulated and unclear label ‘cruelty-free’) increased by 7.5% and dairy products with animal welfare claims increased by 3.3% from 2020-2021. During the same period, grass-fed and pasture-raised claims across meat categories increased by 7.4% and 4.3% respectively15. Meat and dairy incumbents continue to bend the rules, with limited enforcement. Ben and Jerry’s, owned by Unilever, changed its packaging in 2020 following a lawsuit to remove the claim that its ice cream comes from ‘happy cows’16. Meat producer Tyson announced earlier this year that the ‘no antibiotics ever’ claim on their packaging will be replaced with ‘no antibiotics important to human medicine’17. Tyson also came under fire in 2022 when an undercover audio exposed that their ‘free-range claim was meaningless’18. Tyson and Sainsbury’s have been under scrutiny again recently with their new offering of ‘climate-friendly beef’ which allegedly leads to 25% less GHG emissions compared to standard beef. Despite requests, the companies have not offered any proof to support their claims.

It is hard to understand where regulators draw the line. If three definitions and variations of ‘organic’ are acceptable, why is ‘plant-based’ or ‘animal-free’ assumed to be more difficult for the consumer to understand? A survey conducted by ProVeg found that 94% of people are not confused by plant-based chicken items being labelled as nuggets. Similarly, 80% stated that it is obvious that products labelled as vegan, vegetarian, or plant-based are free from animal meat19. As per the diagram above, it is surprising that while food labelling is regulated for alternative protein products, it is leading to more ambiguity and less clarity. If regulations were created to protect consumers, it would appear they can be simplified. One such example of clear labelling regulation hails from India. Given the large vegetarian population, India’s Food Safety and Standards Regulations require all vegetarian food items’ packaging to include a unique symbol, a green-coloured square with a green dot in the centre. Similarly, food containing eggs or meat is expected to bear a red square with a red triangle in the middle. This simplified labelling ensures that everyone can clearly tell the contents of the product without having to comb through the fine print.

A More Perfect Label

We are entering an era of greater product choice and complexity. Regulators must respond with simple, fair, universal labelling guidelines that not only protect consumers but recognize that they want to choose products that match their values and preferences. At the same time, better enforcement of the currently regulated labels will heighten consumer protection and prevent abuse of marketing claims. The label is indeed an effective marketing tool, but one that should only be made available with accurate and consistent information. Regulations evolve, as do consumer preferences. We have come a long way from calling ice from refrigerators ‘artificial ice’, or insulin created in a lab ‘artificial insulin’. It’s time we recognized that there are a variety of ways to meet consumer preferences and create labelling guidelines to match those standards.

FDA Food Labelling and Nutrition, Food Allergies

Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI)

Food Dive, Bill labelling plant-based meat as ‘imitation’ proposed in Congress

FDA

Vegconomist

GFI Europe

Plant-Based News

Food Standards Australia and New Zealand (FSANZ)

Food in Canada

Food Navigator

USDA, Understanding the Organic Label

USDA

Singapore Food Agency (SFA)

Food and Beverage Industry News

Food Navigator

Reuters

CNN News

Vox

Vegconomist